Civic Solidarity Platform's anti-torture working group presents its second Index on Torture

In 2020, the Working Group developed the Index and conducted the first pilot measurement in 8 countries of the OSCE region. The Index was calculated for each country based on a series of measurements reflecting the State's performance in areas such as torture response mechanism, judicial review, anti-torture provisions in domestic legislation, procedural guarantees designed to prevent the use of torture, torture prevention mechanisms and methods available in the country and the State's adherence to international standards on the prohibition of torture.

Following the pilot measurement, the Working Group held a series of consultations to review the Index parameters for a more comprehensive approach to assessing the situation in each country. As a result, a number of methodological adjustments were made, e.g. certain indicators were added or refined and criteria were balanced to reflect both the regulatory framework and the law enforcement practice. In addition to this, a new section was added in which the effectiveness of torture investigation is assessed based on surveys of relevant experts, such as lawyers, prosecutors, judges, criminal investigators and human rights defenders.

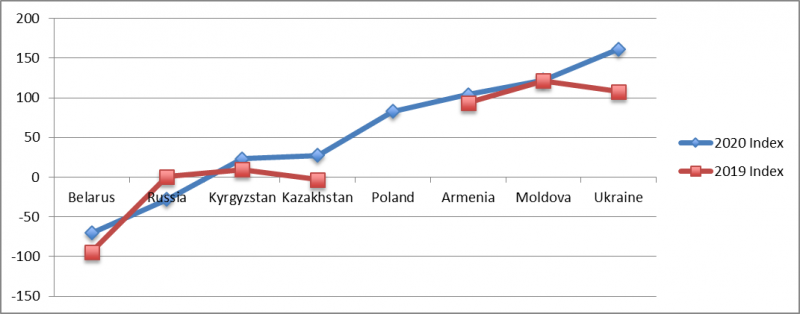

Here, we present the 2020 Index measurement results from eight countries of the OSCE region: Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Poland, Russia, and Ukraine.

| 2020 | 2019 | |

| Belarus | -70.1 | -94.2 |

| Russia | -27.97 | 0.81 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 23.08 | 9.45 |

| Kazakhstan | 27.25 | -3.04 |

| Poland | 82.67 | - |

| Armenia | 104 | 93.77 |

| Moldova | 122.21 | 121.26 |

| Ukraine | 161.1 | 107.83 |

It is worth mentioning a significant increase in the Index value for certain countries. The first and most obvious reason for such increase is the review of the Index, which included reformulation of certain parameters and introduction of new ones. In particular, according to Belarusian experts, the updated definitions make certain indicators more flexible and allow the researchers to address both the positive and negative aspects of relevant laws and enforcement practices and thus to acknowledge useful legal provisions as well as omissions; in particular, the experts attribute the country's higher Index score with the review and addition of indicators in the sections on the investigating authority and torture criminalization in Belarusian law: while the Criminal Code does not explicitly prohibit torture, the Constitution contains a definition and a prohibition of torture which are in line with the international standards; however, there is no punishment for the use of torture. The significant growth of the Index for Kazakhstan was primarily due to a change in the situation with the openness of data on the number of torture complaints. For 2019 Index the experts noted the absence of such data, for current Index they indicated that the data can be provided upon request to state bodies.

Second, certain countries have reported substantive changes in the situation with the prohibition of torture. For example, according to Ukraininan experts, the country's law enforcement agencies have recently focused more on the proper recording, use, storage and access to CCTV footage and on the procedural safeguards granted to detainees – such as allowing a phone call to relatives, advising on the availability of free legal aid and asking about any health complaints – where detainees report health problems, the police call an ambulance to decide whether further detention or hospitalization is possible.

Russia is the only country which saw a drop in its Index score by almost 30 points since the previous year. The change happened because of the clarification of parameters in the Judicial Review and National Regulations/Criminalization sections. While back in 2019, at least some statistics on sentencing were available upon request to human rights defenders, currently, the authorities either refuse to provide such statistics or give meaningless and formalistic responses instead. Thus, the introduction of additional indicators to measure effective protection and safety of torture victims caused Russia's aggregated Criminalization indicator to drop significally. This means that although Russian law does contain criminal sanctions for torture, its victims are poorly protected from pressure, abuse and retaliation in the form of prosecution for allegedly false accusations, while domestic courts refuse to properly address such situations.

The overall distribution of the Index scores across countries remains similar to the one reported in the previous year. Moldova left the position of the leader in the Index. For several refined indicators, in particular, the provision of procedural guarantees, the indicator of this country has increased, but then in the section concerning the provision of video recording and the availability of publicly accessible information on the regulation of video surveillance, Moldova dropped to the second place, since the country does not have publicly available information on regulating the use of video monitoring.

Just as before, the main challenge faced by human rights defenders in compiling the Index is a lack of comprehensive, clear and regularly updated information on these issues in the public domain, while attempts to obtain this information by sending inquiries to relevant authorities tend to be futile in a number of countries. For example, in Russia, no statistics were provided in official responses to such inquiries, while in Kazakhstan, the responses received from different departments contained different data on the same indicators.

Therefore, certain parameters of the Index for six countries were not included in the aggregated Index. More specifically:

- No clear and coherent statistics is available on the number of torture complaints, criminal investigations opened, and torture cases brought to court in Belarus, Kazakhstan, Poland and Russia;

- The workload faced by criminal investigators is impossible to estimate with any degree of accuracy in almost all countries covered by the Index, due primarily to the absence of data on the number of investigators working on torture cases. The only exceptions are Armenia (8-9 cases per investigator) and Ukraine (34 cases per investigator);

- No clear and consistent information is available either in the public domain or upon request on the number of torture complaints, criminal cases initiated and criminal cases investigated and brought to court in Belarus, Kazakhstan, Poland and Russia. The lack of such information makes it impossible to assess how many torture investigations have been completed and whether the investigating body is competent to go ahead with the investigation where the victim does not report torture or withdraws the report.

Working Group members from the following eight countries contributed to the Index preparation:

Promo-LEX Association, Moldova

Association of Ukrainian Human Rights Monitors on

law enforcement

Helsinki Citizens' Assembly-Vanadzor, Armenia

Voice of Freedom, Kyrgyzstan

Committee against Torture, Russia

Human Rights Movement Bir Duino, Kyrgyzstan

Viasna Human Rights Center, Belarus

Kadir Kassiyet, Kazakhstan

Public Verdict Foundation, Russia

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights, Poland