Pressuring political prisoners in Belarus: Censorship of correspondence and isolation

Blocking prisoners' correspondence has become a tactic to pressure political prisoners and their supporters in Belarusian prisons and pre-trial detention centers. Previously employed in select facilities, this practice now extends across all institutions amid the ongoing war conflict in Ukraine. After sentencing, political prisoners can only receive letters from immediate family members listed in their personal files. The rules governing correspondence in detention centers lack logic, with letters selectively blocked both from relatives and from unrelated individuals, leaving some prisoners with little to no communication.

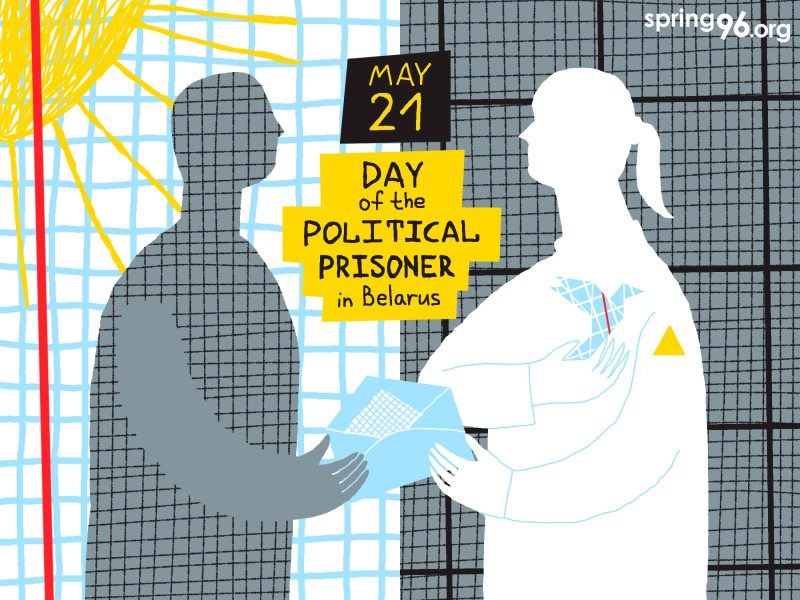

Human rights defenders choose the right to correspondence as the central theme of this year's Day of Solidarity with Belarusian Political Prisoners. On May 21, Viasna calls on everyone to stand in solidarity, raising awareness of the prisoners' plight and demanding their release.

May 21 is the Day of the Political prisoner in Belarus: show your solidarity and join the action in your city

Selective censorship: Arbitrary blocking of letters in detention centers

In pre-trial detention centers, censorship of correspondence occurs selectively, depending on individuals or cells, influenced by censors' moods or investigators' orders. Many political prisoners reported receiving few letters during their initial month of detention. Uladzimir Labkovich faced difficulties corresponding with colleagues, acquaintances, and sympathetic Belarusians. According to Nina Labkovich, the political prisoner's wife, even correspondence with family members was irregular.

“Our letters arrived sporadically. There was a month without any mail. [But] Uladzimir writes letters every day,” she noted.

Another former political prisoner shared how his letters didn't reach anyone during the first month, with only around 30 out of 120 letters reaching their destinations in four months.

Kanstantsin Yarshou, like many other former political prisoners, highlighted the poor situation regarding letters in Detention Center No. 1 in Belarus. He recalled instances when their letters didn't reach anyone:

"Many letters didn't reach inmates in our cell, especially those labeled as ‘political’. However, people fear ending up in solitary confinement and aren't actively fighting for their correspondence. Political prisoners often face difficulties with mail, but receiving letters is such a pleasant surprise!”

Darya Karol remembered being in a cell where mail delivery was good. She wrote letters every day, even if she didn't receive any in return:

“I once had a week when I only received three letters, which was my worst week in terms of correspondence.

However, censorship of letters serves as a tool of pressure. In Palina [Palavinka]'s case, an investigator restricted her correspondence. For example, she would receive her third letter from her sister, and the next one would arrive as the ninth. However, her letters always reached her relatives.

Volha Piatukh faced a similar situation. She could only receive two letters per week—from her mother and father. She didn't receive any more letters. She knew she was entitled to two letters per week and didn't expect any more.”

Hanna Vishniak shared her recollections while in the Valadarka facility in Minsk. Her mother was infected with COVID-19 for 29 days, but her letters were not given to Vishniak:

“Every morning, I wondered if my mother was still alive. Eventually, I shouted at the operative, and he couldn't bear it and brought me her letter. When I found out my mother was alive, I jumped up and hugged him. Shortly after that incident, he resigned—perhaps unable to continue working after witnessing it all.”

There have been cases of pressure on political prisoners regarding the content of their letters. Vital Zhuk, for instance, revealed that in Babrujsk Penal Colony No. 2, prisoners were sent to the punishment cell over information about the Ukrainian army's successes in the war.

“If someone wrote in a letter and then you go around the unit and say how good Ukrainians are and how they are winning the war, or were able to give a decent fight to the Russians, you will be immediately removed from the living area for such news”

In any Investigative Isolation Facility (including Akrestina), letters do not reach the prisoners at all.

Violation of rights: Breaking international standards and national laws

Human rights lawyer Pavel Sapelka says that the blocking of correspondence is not new and has been used against political prisoners in the past, but its use has increased after the events of 2020. According to him, this practice has several aims. Firstly, it makes the conditions for serving sentences harsher. Secondly, it punishes relatives and close ones who cannot communicate with the person. Lastly, it creates an informational vacuum around political prisoners, making them believe they are forgotten and their cause worthless, which is far from reality.

Such practices violate international law, rules for the treatment of prisoners, and national legislation. According to the latter, restrictions on correspondence can be imposed only for lawful purposes such as preventing pressure on defendants or leaking secret information. But current practices have different objectives, including isolating prisoners from the outside world, a state known as "incommunicado."

The only hope is that at least some of the letters reach the recipients, and occasionally, some prisoners manage to receive letters for a brief period. Regardless, writing letters to political prisoners is vital, showing prison administrations the continuous attention and interest of society and civil institutions in supporting the incarcerated.

The United Nations' Minimum Standard Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Nelson Mandela Rules) and the Criminal Executive Code of Belarus provide guidance for prisoner correspondence. According to these, prisoners should be allowed to send and receive letters and telegrams without restricting quantity. However, the actual practice within Belarusian prisons often deviates from these rules.

The Internal Regulations of correctional institutions and pre-trial detention centers in Belarus authorize censorship of prisoner correspondence. Any letters that contain coded messages, insult, or pose harm to the rights of state bodies, public associations, or individual citizens are prohibited. Also, any information that can hinder a preliminary criminal investigation or trial, encourage a crime, or constitute a state secret, is not allowed.

The situation is grim, with the authorities actively violating the rights of political prisoners. And while it's essential to hold those responsible accountable, the reality is that these practices happen not just with the knowledge of the higher authorities but under their direct orders.

Nonetheless, the continuous attention and support from civil society and human rights organizations worldwide can make a difference. It's crucial to keep shedding light on the situation, advocating for justice, and supporting the prisoners and their families in these challenging times.