To Make Bialiatski Better Known than Obama: How Europeans Are Fighting for Belarusians

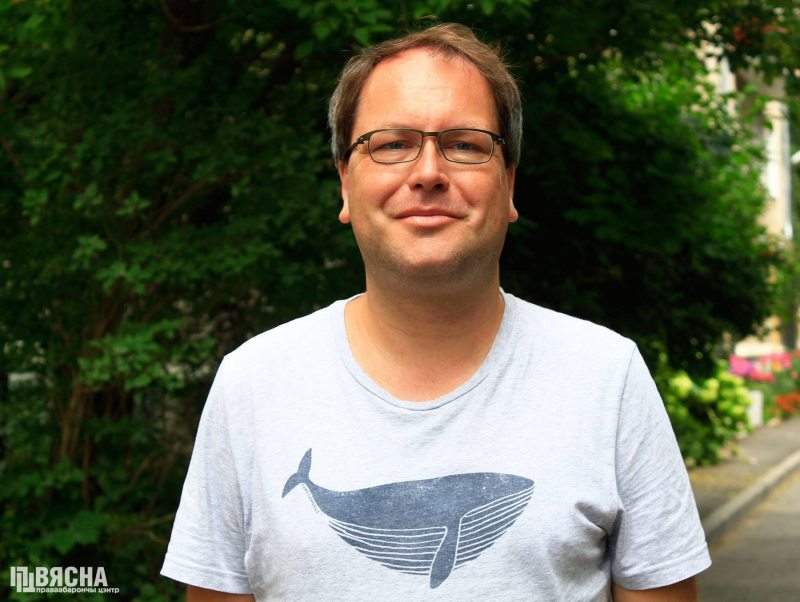

Thanks to the Swiss-German human rights organization “Libereco - Partnership for Human Rights”, European parliamentarians are becoming godparents for Belarusian political prisoners. In turn, every Belarusian judge receives a letter in their mailbox with a reminder of what he or she should actually be doing. The chairman of the international human rights organization “Libereco — Partnership for Human Rights”, Lars Bünger, has been involved with Belarusian issues for more than 20 years. He gave a big interview to Euroradio, where he spoke about his human rights journey, the fight for Belarusian political prisoners and the solidarity campaign #WeStandBYyou.

"I thought there would be several hundred political prisoners in Belarus. But I didn't think there would be 1,500 of them."

— You founded Libereco in 2009 - at that time the European media were still very reluctant to write about Belarus. Why did you become interested in our country?

— I first came to Belarus in the summer of 2000 with my scout friends. It was my first personal encounter with Belarusians and Belarusian politics. And then I found myself visiting again and again, summer after summer, as a volunteer. And year after year, I kept getting closer to Belarusians.

I was still a student then, and in Bonn we had a student group Amnesty [Amnesty International — Euroradio]. We were working on various topics, and among them we encountered the topic of the "ZUBR" youth movement in Belarus. Activists of this movement were facing pressure from the government, and Amnesty was working on their cases.

We were visiting Belarus, contacting the Viasna Human Rights Centre and other activists. And then we found out that Bonn is also a twin city of Minsk. And so, step by step, the pieces came together.

But after finishing our studies, we realized that Amnesty could not focus on Belarusian issues the way we would like to. They do a lot, but we wanted a more direct contact with Belarusian human rights defenders and activists. And that's when we founded Libereco, a new organization that could deal with issues that Amnesty does not deal with. By the time Libereco was created, many of its founders, including myself, had been already working on the issue of human rights in Belarus for many years in other organizations.

From the very beginning, we were dealing with the issue of political prisoners in Belarus, and we were working with it especially actively after the 2010 presidential campaign. Then we initiated a campaign, similar to the one that exists now: "godparents" for political prisoners in the parliaments of European countries.

After the 2015 election, there was a lull, and we temporarily focused on other issues, for example, on the issue of the homeless in Belarus. But in 2020, even before the election, we noticed that new political prisoners were appearing in the country. And in the summer of 2020, we launched the "godparents" for political prisoners initiative again. It means that we contact members of parliaments across Europe with a request to pay attention to political prisoners in Belarus, "adopt" one of them and start advocating to have them released from prison.

— Did you expect that 2020 would turn out the way it did in Belarus?

— When we started this campaign, I assumed that the situation in 2020 would be a little worse than in 2015. I thought that there would be several hundred political prisoners in Belarus. But I could not imagine that there would be more than one and a half thousand of them. And we are talking only about those who are officially recognized as political prisoners! No one expected this.

Now we already have 400 parliamentarians involved in the fate of political prisoners in Belarus, and we are carrying on with the campaign. We get a lot of support from across Europe. Why are we doing this? Because we cannot accept that such a dictatorship still exists in Europe, very close to us. And this dictatorship throws innocent people into prisons, people who did nothing wrong!

They did not steal anything, they did not kill anyone; innocent people were imprisoned only because they do not support Lukashenka's regime. Students, workers; ordinary people like you and me. We simply cannot allow this to keep happening in Europe again and again.

Now it is very important that they are not forgotten. Because the war in Ukraine is a new level of disaster, and so is what is happening in Israel and Palestine now. The attention of all the media has turned to military conflicts. This means it is now even more important to remind them: in Belarus, one and a half thousand political prisoners are still behind bars.

What do the “godparents” know about their “godchildren”?

— Speaking about the "godparents": sometimes we are approached by relatives of political prisoners who say that their “godparents” have never contacted them or sought to find out how they could help. Did you hope for such direct contacts between parliamentarians and the relatives of political prisoners when you founded this initiative?

— The main thing we wanted was to show support for Belarusian political prisoners from the side of European parliamentarians. To remind the Belarusian authorities that these people are not forgotten: we know their names, we follow their cases. That is the main goal of this campaign.

And then a lot depends on the parliamentarians themselves. Some of them may want to do more. A lot depends on the country, on whether the politician works full-time in the parliament (for example, in Switzerland it is a part-time job). It depends on how many colleagues the parliamentarian has. Many of them don't have assistants and have to do all the work themselves, so they really do have a busy schedule.

And yet, some of them do more than we envisioned. They may attempt to get in touch with the Belarusian authorities, the embassy, and relatives. If the relatives have a need to contact the "godparents", they can contact us directly or contact the Viasna Human Rights Centre, and we will try to inform the parliamentarian about their request.

— Within the initiative of Libereco, twenty human rights organizations from 10 countries signed a letter that was sent to 413 Belarusian judges. Did you get a reply?

— We did not receive a response from these judges; nor did we expect one. Each of them received our letter. And that is a warning. I think that all the judges, all the prosecutors, all the prison employees, the police and the KGB must be aware: we know about their crimes.

They must understand: many human rights organizations are currently collecting evidence of their crimes. And the day will come when the dictatorship falls and Belarus becomes a democratic country. And then everyone responsible for arresting and torturing innocent people will be brought to justice. And these letters are our warning to these judges. It is a reminder to them: they are committing a crime by sending innocent people to prison.

But they can quit their job, they can move to another country; they are under no obligation to continue breaking the law. Otherwise, one day they will be brought to justice.

— Thanks to Libereco, the name of one of these political prisoners — Ales Bialiatski — can be heard on European streets. But when you go to a rally carrying his portrait, how many Europeans recognize the Nobel Peace Prize laureate’s face?

— Unfortunately, not so many. But I think this situation is similar for many Nobel Peace Prize laureates of recent years, unless it's Barack Obama. Try asking people who won the Nobel Peace Prize two weeks ago. Even I only remember that she is a human rights activist who has fought for women's rights in Iran; but right now I cannot remember her name off the top of my head [we remind readers that this year's Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Narges Mohammadi — Euroradio].

This is exactly why we organize so many events in support of Ales Bialiatski. Yes, we use this award to draw attention to his plight, and to that of the other political prisoners in Belarus. And the reaction on the streets is very positive: a lot of people approach us, talk to us and assure us that yes, they know what is happening in Belarus, even though it is an issue that no longer receives much media coverage. And they thank us for showing people’s faces: we have big banners with political prisoners’ portraits.

It attracts attention, and people see how many political prisoners there are in Belarus. And that is precisely our goal: to show how many people have been affected.

— Have the Belarusian people done enough to no longer be asked: “Belarus? Where is that?” What do we need to do for everyone to remember that Belarus is in Europe?

— I think Belarusians do not need to prove that they are a part of Europe. They definitely are. And if any proof was needed, everything was already proven in 2020. People came out to protest. It was obvious to the entire world, not just Europe: they want democracy and freedom, they want to be part of the European community. They are a part of the democratic community, and there is no need to prove anything else.

I have known Belarus long enough. After 2010, it seemed to me that Belarusians were depressed. They did not want a war like in Ukraine. They decided: “Okay, we have Lukashenka, but at least we don’t have a Russian invasion”. And in 2020, I saw people who showed that they also want freedom, they want democracy.

Yes, I was surprised that the older generation supported the dictatorship. But the Belarusians simply did not have a chance to try to build democracy, like in Europe, where democracy has existed for decades. You had the Soviet Union, then a few years of democracy, and then Lukashenka came to power. There was simply no time for democracy to take root.

But the younger generation knows how their neighbouring countries live.

Every time I visited Belarus starting in 2020, I saw that my friends in Belarus had the same dreams as me, they listened to the same music as me, they wanted the same for their families, they were looking for the same things at work. They are just like me. And it has long been clear to me that Belarusians of my generation have the same picture of the world as I do.