Restricting civil society participation in OSCE a tremendous setback for Helsinki process, says CSP

“Restricting civil society participation in the work of the OSCE would be a tremendous setback for the Helsinki process and a betrayal of the spirit and founding values of this unique peace advancement initiative,” says an appeal by the Civic Solidarity Platform, a network of more than 90 human rights NGOs from throughout the OSCE region.

The text was published following the 2017 OSCE Parallel Civil Society Conference in Vienna on 5-6 December. The event is traditionally held on the eve of the OSCE Ministerial Council Meeting. The appeal has been signed by over 50 NGOs, including the Barys Zvozskau Belarusian Human Rights House and the Human Rights Center “Viasna”.

“For four decades, civil society groups have played a crucial role in monitoring, documenting and reporting on the implementation of the human dimension commitments undertaken by participating States in the framework of the Conference and later the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. By engaging with the OSCE, NGOs have helped to keep human rights high on the agenda, mobilize attention to human rights crises and shape OSCE action on pressing human rights issues. Now some governments, which have adopted legislation and policies restricting civil society activities in their own countries, are pushing for new rules and regulations to limit civil society participation at the level of the OSCE. Introducing measures to this end would negatively and irreversibly affect the OSCE’s credibility at a time when civil society actors are facing unprecedented pressure across the region and, more than ever, need OSCE forums to make their voices heard,” CSP said.

The appeal highlights a “growing trend of shrinking and even closing civil society space in many countries of the OSCE region,” with governments exploiting “security concerns to justify far-reaching restrictions on civil society and to crack down on NGOs that work on “sensitive” issues, in particular human rights.”

“Among others, states have denied registration and forced NGOs to close down, labelled them “foreign agents”, and prosecuted their leaders using broadly worded extremism and terrorism legislation that does not meet the fundamental principle of legality and can be applied to conduct that has nothing to do with violence. Human rights groups and defenders working to promote women’s rights, minority rights and the rights of vulnerable communities have in particular been singled out for persecution,” it said.

The same negative trends are mentioned in the Civic Solidarity Platform’s recommendations to the participants of the Ministerial Council Meeting, a set of “outcome documents” covering key issues of concern in the OSCE region.

“These extremely worrying tendencies have persisted throughout 2017, continuing unabated in countries like Azerbaijan and states in Central Asia, escalating further in Russia and Turkey, and spreading to new countries where until recently civil society was able to work without obstructive state interference. In particular, space for civil society visibly shrank in Poland, Hungary, Ukraine, Italy, and the USA, to give but a few examples,” the document said.

Speaking of specific cases of persecution of human rights defenders in the post-Soviet region, CSP stresses the alarming reports coming from Azerbaijan, where a new wave of arrests of government critics has taken place in recent months.

In Russia, Valentina Cherevatenko, chair of the CSP member organization Women of the Don, became the first NGO leader the country to face criminal charges over non-compliance with the notorious “foreign agents” law.

Critics of Russia’s unlawful annexation of Crimea also face persecution. Among them are journalists and minority leaders.

In Ukraine, activists who fight against corruption, advocate for environmental and land rights, promote LGBT rights or work in the conflict zone in Donbas, have been subjected to intimidation and harassment.

A series of human rights defenders, civil society activists, trade union leaders, journalists, social media users and other critics have recently faced criminal charges in Kazakhstan.

In Turkmenistan, civil society groups have documented over 100 cases of enforced disappearances in prison of individuals convicted in unfair and politically motivated trials. The total number of such cases is likely to be much higher.

In Uzbekistan, as of mid-November 2017, at least ten human rights defenders, journalists and government critics had been released since current President Shavkat Mirziyoyev came to power in September 2016 after the death of long-time ruler Islam Karimov. However, many others remain behind bars.

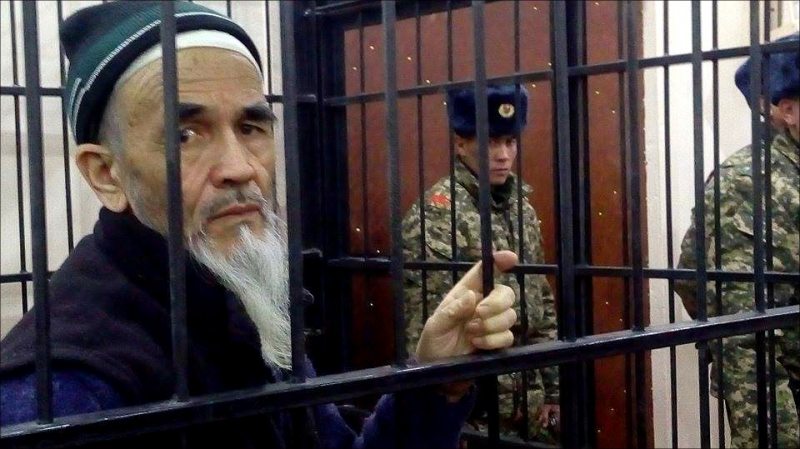

Similar cases have also been reported from Tajikistan, where two lawyers received prison sentences of over 20 years, and Kyrgyzstan, where the life sentence of human rights defender Azimjan Askarov was upheld at a re-trial.

The Belarus section mentions the case of the REP trade union leaders, Henadz Fiadynich and Ihar Komlik, the existence of two political prisoners, Dzmitry Paliyenka and Mikhail Zhamchuzhny, as well as the persecution of “lawyers working on politically motivated and human rights related cases”, including the disbarment of Hanna Bakhtsina.

CSP also voices concerns over lack of access to justice for the victims of enforced disappearances and their families.

“In Belarus, in the end of 1990s, a secret group of former special services officers was created by high-level government officials for the purpose of assassinating dangerous criminals and political opponents of the regime. This was to be done by total annihilation of the bodies or hiding them without trace. In 1999-2000, four high-profile cases of disappearance and alleged murder of political opponents of the government took place, including a former deputy prime minister, a former minister, a leading journalist, and a businessman who provided support to the opposition. The official investigation carried out in these cases was inefficient and failed to establish the circumstances of the crimes and identify the perpetrators. These cases were in the focus of attention of a special report by the PACE Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights in 2004 and of the OSCE Moscow Mechanism report on Belarus in 2011. The UN Human Rights Committee reviewed individual complaints by the relatives of the disappeared and concluded that Belarus must carry out a full, impartial and thorough investigation, bring the perpetrators to justice, pay compensation to the relatives, and make public the findings. However, the government replied that it does not recognise competence of the Human Rights Committee to review individual complaints and took no action,” it said.

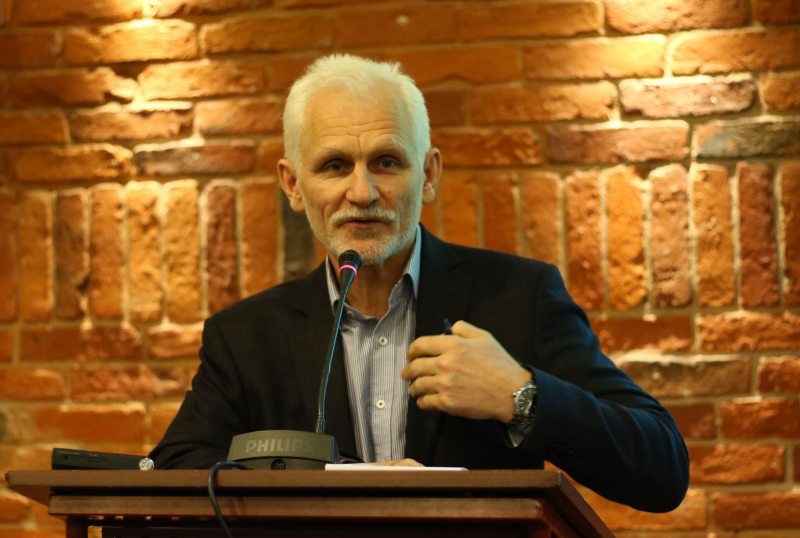

Chairman of the Human Rights Center "Viasna" Ales Bialiatski, who participated in the OSCE Parallel Civil Society Conference, said that the recommendations were passed to the countries’ delegations and, most importantly, the Italian delegation, which will chair the OSCE in the coming year of 2018.

“In recent years, the human rights situation in the OSCE area has deteriorated significantly,” Bialiatski said. “And it has not improved in Belarus, either. But the general trend in the OSCE region brings more anxiety than optimism. Nevertheless, we will continue to influence the Belarusian authorities through international mechanisms to ensure that they comply with international obligations in the field of human rights that they themselves undertook. We need to follow best practices, rather than copy the examples of the worst satrapies,” says the human rights activist.